Isolated capitellar fractures are rare. It accounts for only 1% of all elbow fractures and 3-4% of distal humeral fractures. These fractures are almost exclusively seen in those older than 12 years of age. The annual incidence is reported to be 1.5 per 100 000 population, and the incidence is highest in women over the age of 60. Capitellum fracture was first described in 1841 by Cooper. Reports by Hahn in 1853, Kocher in 1896, Steinthal in 1898 and Lorenz in 1905 lead to better understanding of the pathoanatomy.

The commonest cause of this injury is a fall on the outstretched hand with an extended or semi flexed elbow from the standing height. Young males may present with high velocity injury like fall from height or motor vehicle accidents. The most accepted mechanism is the transmission of an axial force through the radius head and lateral ridge of trochlea. As the center of rotation of the capitellum is 12–15 mm anterior to the humeral shaft, it is vulnerable to shearing fractures in the coronal plane. Most series report a female preponderance of 4:1. This may be due to the increased carrying angle and hyperextension in females which could lead to greater contact force transmission to the lateral column.

Clinical Features

Patients clinically present with pain, minimal swelling and tenderness on the lateral side of the elbow. Elbow movements and forearm rotation will be limited due to pain. Capitellum fractures may occur in isolation or may be associated with elbow dislocation, ligament injury or fractures such as radial head.

Imaging

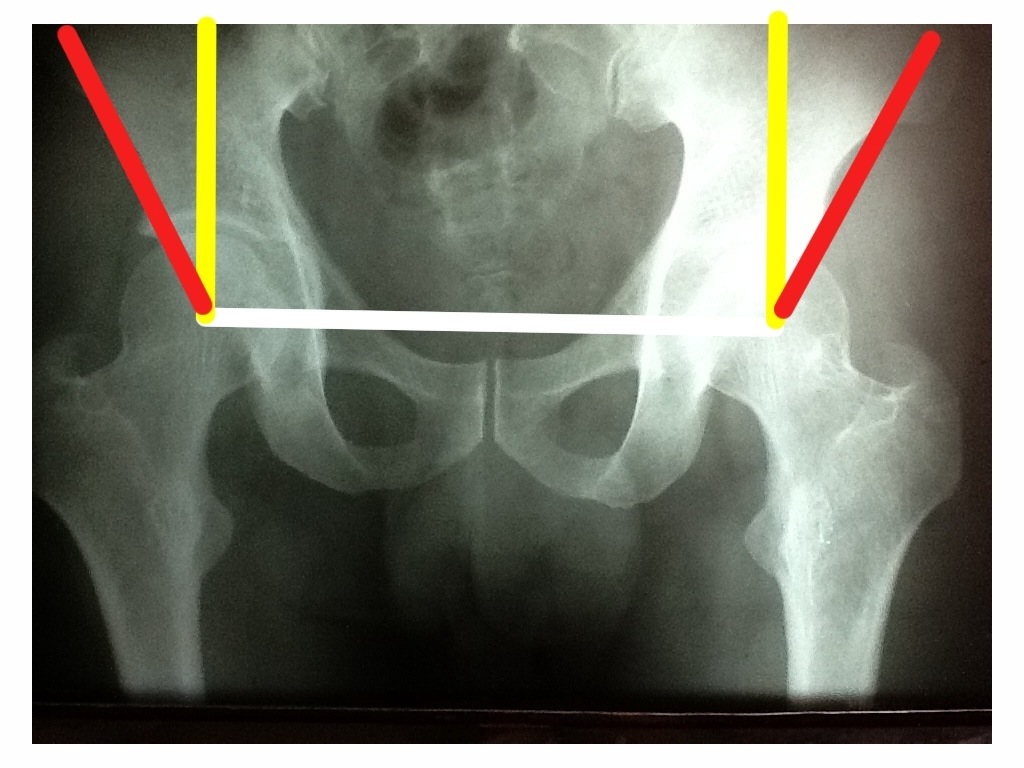

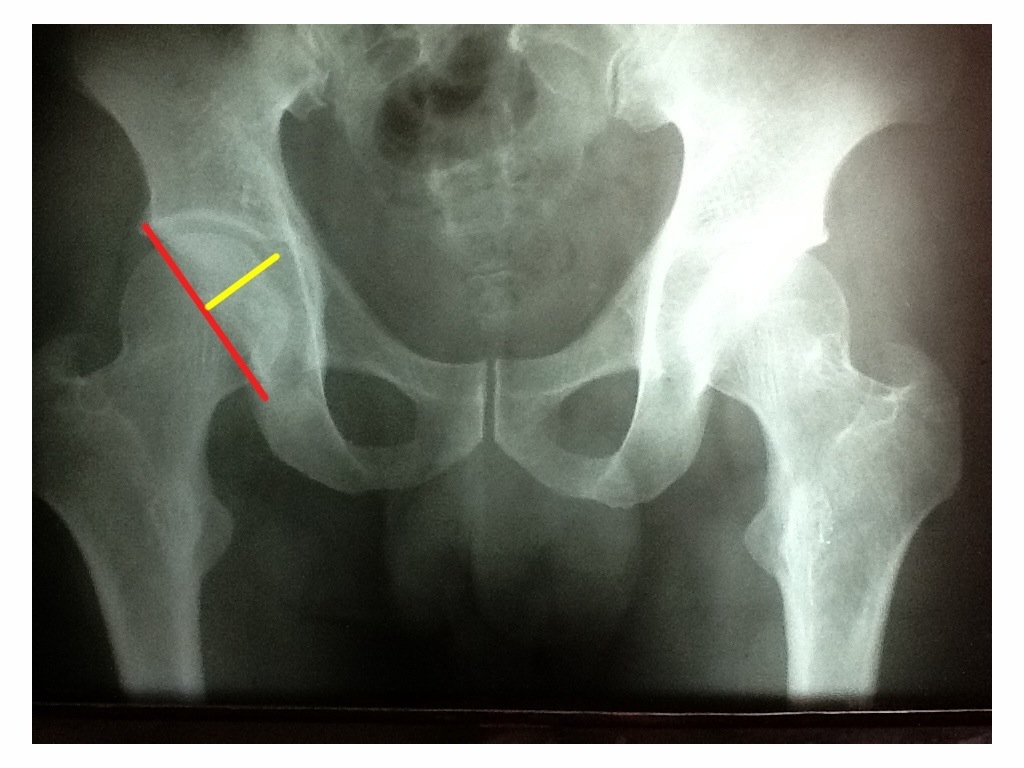

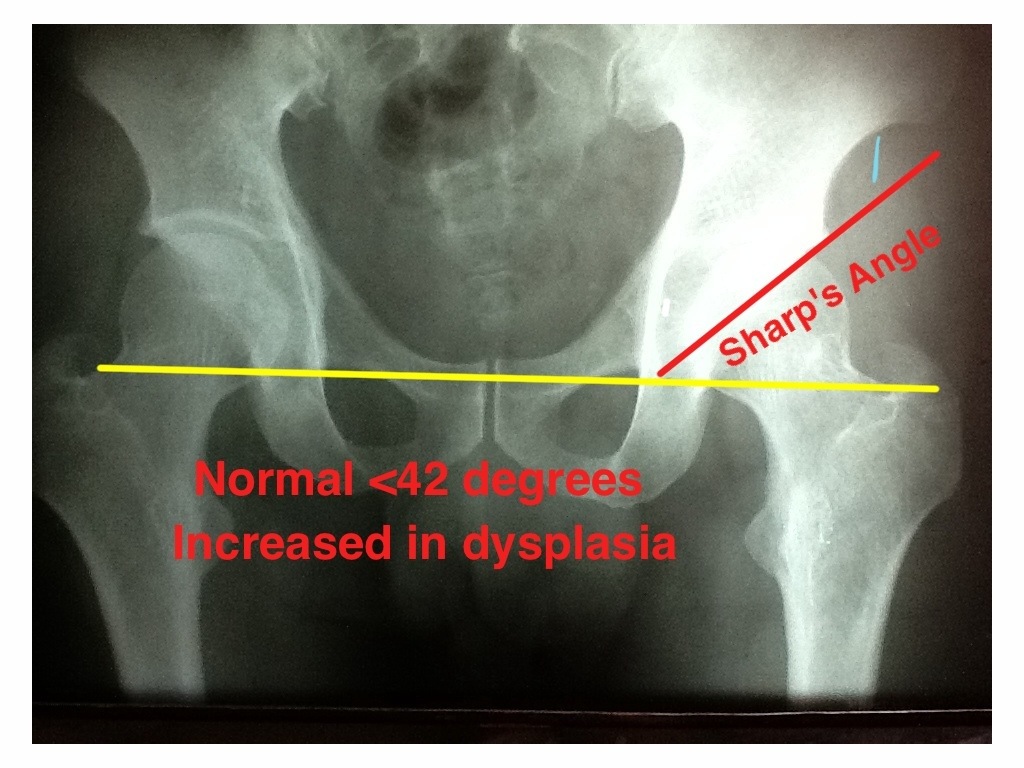

The diagnosis is confirmed by the lateral view of the joint, which will show the semilunar fragment displaced anteriorly and superiorly. Careful look at the x-ray is necessary for diagnosis which is missed many a time. The AP view may appear normal. On the AP view if the subchondral line is traced from medial to lateral, it will show haziness or discontinuity in the lateral portion. In case of type 4 fractures in which the fragment has capitellum and the lateral half of trochlea, “Mckee’s double arc sign” is seen. The two arcs are due to the subchondral bone of capitellum and trochlea.

Fractures that appear to involve the capitellum alone are often in reality much more complex. Plain radiographs often underestimates the true extent of the injury and computed tomography with 3D reconstruction is a great tool for better understanding of the injury pattern. CT scans with three-dimensional reconstruction help in assessment of the size and the orientation of the fracture fragment and in guiding the preoperative planning.

Classification

Bryan and Morrey classification

Type I (Hahn-Steinthal fracture) – Shear fracture involving a large osseous portion of the capitellum in the coronal plane and less than half of the lateral part of the trochlea.

Type II (Kocher-Lorenz fracture) – Fracture involves a shell of the articular cartilage with a thin layer of bone.

Type III – Comminuted fractures.

Type IV (McKee modification) – Hahn-Steinthal type fracture that includes more than the lateral half of the trochlea.

The type I fracture is typically associated with the anterior displacement of the fracture fragment and the type II fracture fragment is usually displaced posteriorly.

AO classification

Distal humeral articular fractures are grouped as B3 (distal humerus, partial articular, and frontal)

B3.1 – Capitellar fractures

B3.2 – Trochlear fractures

B3.3 – Capitellar and trochlear fractures.

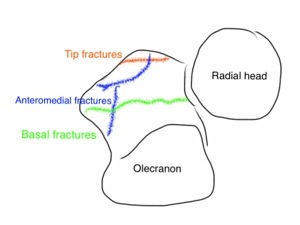

Ring Classification

According to this classification, fractures of the distal humeral articular surface which do not involve the medial and lateral columns are often more extensive than is evident from plain radiographs. According to them, the distal humeral articular fractures have five anatomic components:

The capitellum and the lateral aspect of the trochlea .

The lateral epicondyle.

The posterior aspect of the lateral column.

The posterior aspect of the trochlea.

The medial epicondyle.

Type 1 – A single articular fragment that includes the capitellum and the lateral portion of the trochlea.

Type 2 – Type-1 fracture with an associated fracture of the lateral epicondyle.

Type 3 – Type2 fracture with impaction of the metaphyseal bone behind the capitellum in the distal and posterior aspect of the lateral column.

Type 4 – Type-3 fracture with a fracture of the posterior aspect of the trochlea.

Type 5– Type-4 fracture with fracture of the medial epicondyle.

Dubberley Classification

Classified capitellum fractures into three types and each of these types into A & B subtypes.

1- Fracture of capitellum with or without lateral trochlear ridge

A- Without posterior condylar comminution

B- With posterior condylar comminution

2- Fracture of capitellum and trochlea as one piece

A- Without posterior condylar comminution

B- With posterior condylar comminution

3- Fracture of capitellum and trochlea as separate pieces

A- Without posterior condylar comminution

B- With posterior condylar comminution

Fractures with extensive posterior comminution of the distal humeral columns require bone-grafting alone or in combination with additional fixation.

Treatment

The short-term complications of these fractures are joint stiffness and instability and the long-term complication is post-traumatic osteoarthritis. In spite of limited soft-tissue attachment to the fracture fragments, osteonecrosis is reportedly rare. For prevention of complications and to maximise the functional outcome the fracture should be anatomically reduced and rigidly internally fixed so that mobilisation can be started early. Different treatment options are available ranging from closed reduction and immobilisation, excision of fragment and open reduction and internal fixation.

Type II lesions may be difficult to fix as the fragment has only a thin shell of bone. In type II lesions, fixation by headless screws may be done if feasible, otherwise excision may have to be done. Type III lesions may be difficult to reduce anatomically and may need excision. Type I Hahn-Steinthal lesions should be anatomically reduced and rigidly internally fixed so that mobilisation can be started early. Typically few soft-tissue attachments remain on the fragment, making closed manipulation and reduction difficult and almost impossible to achieve. In addition, closed manipulation may lead to comminution and may worsen damage to articular cartilage. Hence open reduction and internal fixation is the method of choice for treatment of these difficult fractures.

The surgical approach most commonly used is extended lateral approach, but in case of large trochlear fragment, trans-olecranon osteotomy may be needed.

Extensile Lateral Exposure

Anaesthesia– General or regional with pneumatic tourniquet.

Position– Supine with the arm supported on a hand-table.

Incision– Lateral skin incision centred over the lateral epicondyle or a midline posterior incision with development of lateral flaps.

Surgical plane – In many patients the lateral collateral ligament is injured and the elbow may be opened like a book hinging on the ulnar collateral ligament for the exposure of the articular surface. If LCL is intact, then dissection should be anterior to the LCL. Kocher approach uses the plane between the extensor carpi ulnaris and the anconeus and the Kaplan approach uses the plane between the extensor digitorum communis and the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis. In those patients with a fracture of the lateral epicondyle, the fractured lateral epicondyle can be mobilised and was retracted distally along with the attached common extensor origin and LCL. The extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis are elevated from the lateral supracondylar ridge to improve proximal and anterior exposure. The lateral portion of triceps may be elevated if posterior exposure is needed.

Procedure– The fracture fragments were identified, reduced, and provisionally fixed with smooth 0.045 or 0.062-in (0.889 or 0.157-cm) K wires. Internal fixation of capitellum fractures requires near anatomic reduction and compression at the fracture site. Many methods of fixation have been described including the use of 4mm partially threaded screws, headless screws, bone pegs, Kirschner wires and reabsorbable pins. Depending on the stability of fixation and in the absence of other injuries that preclude early mobilisation, mobilisation can be started to avoid problems of prolonged cast immobilisation.

Kirschner wires will not provide strong compression and as the fixation is not stable, prolonged immobilisation may be needed which may lead to joint stiffness. Fixation by partially threaded screws provide strong interfragmentary compression and stable fixation which allows early mobilization.

The posterior-to-anterior screws have been found to be biomechanically superior to anterior-to-posterior screws. This is because countersinking needed with AP screws damage the subchondral bone and compromise the stability. PA screws also have the advantage of leaving the articular cartilage intact. Fixation by variable pitch headless screws such as Accutrak is biomechanically superior to PA lag screws.

The major advantage of all headless screws, is that the screw is placed within the bone without any outside prominence, avoiding impingement. As these screws are cannulated and use alignment jigs, precise placement of the screw is possible.

Further reading

Bryan RS, Morrey BF. Fractures of the distal humerus. In: Morrey BF, editor. The elbow and its disorders. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1985. p 325-33.

McKee M,Jupiter JB,Bamberger B.Coronal shear fractures of the distal end of the humerus. JBone Joint Surg Am 1996;78 (1):49-54.

Ring D, Jupiter J, Gulotta L. Articular fractures of the distal part of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:232-8.

Elkovitz SJ, Polatsch DB, Egol KA, Kummer FJ, Koval KJ: Capitellum fractures: a biomechanical evaluation of three fixation methods. J Orthop Trauma 2002;16 (7):503-6.

Dubberley JH, Faber KJ, Macdermid JC, Patterson SD, King GJ. Outcome after open reduction and internal fixation of capitellar and trochlear fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:46-54.

Boyd HB. Surgical exposure of the ulna and proximal third of the radius through one incision. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1940;71:86-8.

Kocher T. Operations at the elbow. In: Kocher T, editor; Stiles HJ, Paul CB, translators. Textbook of operative surgery. 3rd ed. London: Adam and Charles Black; 1911. p 313-8. 28.

Kaplan EB. Surgical approach to the proximal end of the radius and its use in fractures of the head and neck of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg. 1941;23:86-92